Princess Monoke and My Neighbor Totoro! Baby Clother

| Spirited Away | |

|---|---|

Japanese theatrical release poster | |

| Japanese | 千と千尋の神隠し |

| Hepburn | Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi |

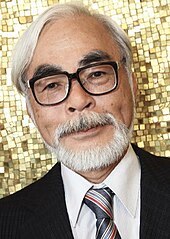

| Directed by | Hayao Miyazaki |

| Written by | Hayao Miyazaki |

| Produced by | Toshio Suzuki |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Atsushi Okui |

| Edited by | Takeshi Seyama |

| Music past | Joe Hisaishi |

| Production | Studio Ghibli |

| Distributed by | Toho |

| Release engagement |

|

| Running time | 125 minutes[1] |

| State | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Upkeep | ¥1.ix–2 billion (United states$15–19.two one thousand thousand)[2] [iii] |

| Box function | $395.viii million [a] |

Spirited Away (Japanese: 千と千尋の神隠し, Hepburn: Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi , 'Sen and Chihiro's Spiriting Away') is a 2001 Japanese blithe fantasy film written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki, blithe by Studio Ghibli for Tokuma Shoten, Nippon Television Network, Dentsu, Buena Vista Home Entertainment, Tohokushinsha Film, and Mitsubishi.[7] The film features the voices of Rumi Hiiragi, Miyu Irino, Mari Natsuki, Takeshi Naito, Yasuko Sawaguchi, Tsunehiko Kamijō, Takehiko Ono, and Bunta Sugawara. Spirited Away tells the story of Chihiro Ogino (Hiiragi), a ten-year-old girl who, while moving to a new neighborhood, enters the world of Kami (spirits of Japanese Shinto sociology).[viii] After her parents are turned into pigs by the witch Yubaba (Natsuki), Chihiro takes a job working in Yubaba'due south bathhouse to find a way to free herself and her parents and return to the human earth.

Miyazaki wrote the screenplay after he decided the picture show would be based on the 10-year-erstwhile girl of his friend Seiji Okuda, the film'south acquaintance producer, who came to visit his house each summertime.[9] At the fourth dimension, Miyazaki was developing two personal projects, only they were rejected. With a budget of US$19 million, production of Spirited Away began in 2000. Pixar animator John Lasseter, a fan and friend of Miyazaki, convinced Walt Disney Pictures to purchase the movie'south North American distribution rights, and served every bit executive producer of its English-dubbed version.[10] Lasseter then hired Kirk Wise as director and Donald W. Ernst as producer, while screenwriters Cindy and Donald Hewitt wrote the English-language dialogue to match the characters' original Japanese-language lip movements.[11]

Originally released in Japan on 20 July 2001 past distributor Toho, the film received universal acclaim,[12] grossing $395.8 million at the worldwide box office.[a] [13] It is frequently regarded as one of the best films of the 21st century as well equally ane of the greatest animated films e'er made.[fourteen] [xv] [16] Accordingly, it became the almost successful and highest-grossing film in Japanese history with a total of ¥31.68 billion ($305 million).[17] It held the record for xix years until it was surpassed by Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba – The Movie: Mugen Train in 2020.

It won the University Award for All-time Animated Feature at the 75th Academy Awards,[18] making it the commencement, and to date only hand-drawn and non-English language-language animated film to win the honour. It was the co-recipient of the Golden Bear at the 2002 Berlin International Motion picture Festival (shared with Bloody Sunday), and is inside the top ten on the British Film Institute'south list of "Acme l films for children up to the historic period of 14".[xix] In 2016, it was voted the fourth-all-time moving-picture show of the 21st century by the BBC, as picked past 177 film critics from around the world, making it the highest-ranking blithe film on the list.[twenty] In 2017, it was likewise named the second "All-time Moving picture...of the 21st Century So Far" by The New York Times.[21]

Plot [edit]

Ten-yr-erstwhile Chihiro Ogino and her parents are traveling to their new abode when her father decides to take a shortcut. The family's motorcar stops in front end of a tunnel leading to what appears to exist an abandoned entertainment park which Chihiro'due south father insists on exploring, despite his daughter's protestation. They find a seemingly empty restaurant still stocked with food, which Chihiro's parents immediately brainstorm to eat. While exploring further, Chihiro reaches an enormous bathhouse and meets a boy named Haku, who warns her to return beyond the riverbed earlier sunset. Still, Chihiro discovers too tardily that her parents have metamorphosed into pigs, and she is unable to cross the now-flooded river.

Haku finds Chihiro and has her ask for a chore from the bathhouse's boiler-homo, Kamaji, a yōkai commanding the susuwatari. Kamaji refuses to hire her and asks worker Lin to send Chihiro to Yubaba, the witch who runs the bathhouse. Yubaba tries to frighten Chihiro away, but she persists, so Yubaba gives Chihiro a contract to work for her. Yubaba takes abroad the second kanji of her name, renaming her Sen ( 千 ). While visiting her parents' pigpen, Haku gives Sen a cheerio card she had with her, and Sen realizes that she had already forgotten her real name. Haku warns her that Yubaba controls people by taking their names, and that if she forgets hers like he has forgotten his, she will not be able to leave the spirit world.

Sen faces bigotry from the other workers; but Kamaji and Lin show sympathy for her. While working, she invites a silent creature named No-Face (Kaonashi 顔無し ) inside, believing him to be a customer. A "stink spirit" arrives as Sen'southward first customer, and she discovers he is the spirit of a polluted river. In gratitude for cleaning him, he gives Sen a magic emetic dumpling. Meanwhile, No-Face imitates the gold left behind past the stink spirit and tempts a worker with golden, then swallows him. He demands nutrient and begins tipping extensively. He swallows two more than workers when they interfere with his conversation with Sen.

Sen sees newspaper Shikigami attacking a dragon and recognizes the dragon as Haku metamorphosed. When a grievously injured Haku crashes into Yubaba'due south penthouse, Sen follows him upstairs. A shikigami that stowed away on her dorsum shapeshifts into Zeniba, Yubaba'southward twin sister. She turns Yubaba's son, Boh, into a mouse, creates a decoy Boh, and mutates Yubaba's harpy into a tiny, flylike bird. Zeniba tells Sen that Haku has stolen a magic golden seal from her, and warns Sen that it carries a deadly curse. Haku strikes the shikigami, which eliminates Zeniba'southward hologram. He falls into the banality room with Sen, Boh, and the harpy on his back, where Sen feeds him role of the dumpling she had intended to give her parents, causing him to vomit both the seal and a blackness slug, which Sen crushes with her foot.

With Haku unconscious, Sen resolves to return the seal and apologize to Zeniba. Sen confronts No-Face, who is at present massive, and feeds him the rest of the dumpling. No-Face follows Sen out of the bathhouse, steadily regurgitating everything that he has eaten. Sen, No-Confront, Boh, and the harpy travel to see Zeniba with train tickets given to her by Kamaji. Meanwhile, Yubaba orders that Sen's parents be slaughtered, but Haku reveals that Boh is missing and offers to retrieve him if Yubaba releases Sen and her parents. Yubaba agrees, but simply if Sen can laissez passer a final test.

Sen meets with Zeniba, who makes her a magic hairband and reveals that Sen's beloved for Haku bankrupt her expletive and that Yubaba used the black slug to take control over Haku. Haku appears at Zeniba'due south home in his dragon form and flies Sen, Boh, and the harpy to the bathhouse. No-Face decides to stay behind and become Zeniba's spinner. In mid-flight, Sen recalls falling years ago into the Kohaku River and being done safely aground, correctly guessing Haku'south existent identity as the spirit of the Kohaku River ( ニギハヤミ コハクヌシ , Nigihayami Kohakunushi ). When they get in at the bathhouse, Yubaba forces Sen to place her parents from amidst a grouping of pigs in gild to break their curse. After she answers correctly that none of the pigs are her parents, her contract disappears and she is given back her real proper name. Haku takes her to the now-dry riverbed and vows to meet her again. Chihiro crosses the riverbed to her restored parents, who do not retrieve anything later on eating at the eatery stall. They walk dorsum through the tunnel until they reach their motorcar, now covered in dust and leaves. Before getting in, Chihiro looks back at the tunnel, unsure if her adventure really happened.

Cast [edit]

Product [edit]

Development and inspiration [edit]

"I created a heroine who is an ordinary girl, someone with whom the audition can sympathize [...]. [I]t'southward not a story in which the characters abound up, only a story in which they draw on something already inside them, brought out past the particular circumstances [...]. I want my young friends to live like that, and I recollect they, likewise, have such a wish."

—Hayao Miyazaki[22]

Every summer, Hayao Miyazaki spent his vacation at a mountain cabin with his family and five girls who were friends of the family. The idea for Spirited Abroad came about when he wanted to make a film for these friends. Miyazaki had previously directed films for small children and teenagers such every bit My Neighbor Totoro and Kiki's Delivery Service, but he had not created a film for x-year-one-time girls. For inspiration, he read shōjo manga magazines like Nakayoshi and Ribon the girls had left at the cabin, but felt they only offered subjects on "crushes" and romance. When looking at his young friends, Miyazaki felt this was not what they "held love in their hearts" and decided to produce the moving picture nearly a young heroine whom they could look up to instead.[22]

Hayao Miyazaki used shōjo manga magazines for inspiration to straight Spirited Away.

Miyazaki had wanted to produce a new film for years, but his two previous proposals—one based on the Japanese book Kiri no Mukō no Fushigi na Machi ( 霧のむこうのふしぎな町 ) by Sachiko Kashiwaba, and another about a teenage heroine—were rejected. His third proposal, which concluded up becoming Sen and Chihiro's Spirited Away, was more successful. The three stories revolved around a bathhouse that was inspired past one in Miyazaki's hometown. He thought the bathhouse was a mysterious place, and there was a minor door next to i of the bathtubs in the bath house. Miyazaki was always curious to what was behind it, and he made upwards several stories nearly it, one of which inspired the bathhouse setting of Spirited Away.[22]

A Japanese dragon ascends toward the heavens with Mount Fuji in the background in this print from Ogata Gekkō. Spirited Away is heavily influenced past Japanese Shinto-Buddhist folklore.[8]

Product of Spirited Abroad commenced in February 2000 on a budget of ¥1.9 billion (United states of america$15 million).[2] Walt Disney Pictures financed ten percent of the film's production price for the right of start refusal for American distribution.[23] [24] As with Princess Mononoke, Miyazaki and the Studio Ghibli staff experimented with computer blitheness. With the utilise of more than computers and programs such as Softimage 3D, the staff learned the software, merely used the technology advisedly so that it enhanced the story, instead of "stealing the show". Each character was mostly hand-drawn, with Miyazaki working aslope his animators to run into they were getting information technology just right.[ii] The biggest difficulty in making the moving picture was to reduce its length. When production began, Miyazaki realized it would be more than three hours long if he made it according to his plot. He had to delete many scenes from the story, and tried to reduce the "eye candy" in the film because he wanted information technology to be simple. Miyazaki did not want to make the hero a "pretty girl". At the beginning, he was frustrated at how she looked "dull" and thought, "She isn't cute. Isn't in that location something we can do?" As the flick neared the end, even so, he was relieved to experience "she will be a mannerly adult female."[22]

Miyazaki based some of the buildings in the spirit world on the buildings in the real-life Edo-Tokyo Open up Air Architectural Museum in Koganei, Tokyo, Japan. He often visited the museum for inspiration while working on the motion picture. Miyazaki had always been interested in the Pseudo-Western style buildings from the Meiji period that were available at that place. The museum made Miyazaki feel nostalgic, "specially when I stand here alone in the evening, near closing time, and the sun is setting – tears well upward in my eyes."[22] Another major inspiration was the Notoya Ryokan ( 能登谷旅館 ), a traditional Japanese inn located in Yamagata Prefecture, famous for its exquisite architecture and ornamental features.[25] While some guidebooks and manufactures merits that the old golden town of Jiufen in Taiwan served as an inspirational model for the film, Miyazaki has denied this.[26] The Dōgo Onsen is likewise often said to exist a key inspiration for the Spirited Abroad onsen/bathhouse.[27]

Music [edit]

The movie score of Spirited Abroad was equanimous and conducted by Miyazaki'southward regular collaborator Joe Hisaishi, and performed by the New Nippon Philharmonic.[28] The soundtrack received awards at the 56th Mainichi Moving picture Competition Laurels for Best Music, the Tokyo International Anime Off-white 2001 Best Music Award in the Theater Movie category, and the 17th Japan Gilded Deejay Accolade for Animation Album of the Year.[29] [30] [31] Later, Hisaishi added lyrics to "One Summertime's Twenty-four hour period" and named the new version of the vocal "The Name of Life" ( いのちの名前 , "Inochi no Namae" ) which was performed by Ayaka Hirahara.[32]

The closing vocal, "Always With Me" ( いつも何度でも , "Itsumo Nando Demo" , lit. 'Always, No Matter How Many Times') was written and performed by Youmi Kimura, a composer and lyre-player from Osaka.[33] The lyrics were written by Kimura's friend Wakako Kaku. The song was intended to be used for Rin the Chimney Painter ( 煙突描きのリン , Entotsu-kaki no Rin ), a unlike Miyazaki film which was never released.[33] In the special features of the Japanese DVD, Hayao Miyazaki explains how the song in fact inspired him to create Spirited Away.[33] The song itself would exist recognized as Gold at the 43rd Nihon Record Awards.[34]

Besides the original soundtrack, there is too an image anthology, titled Spirited Away Image Anthology ( 千と千尋の神隠し イメージアルバム , Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi Imēji Arubamu ), that contains 10 tracks.[35]

English adaptation [edit]

John Lasseter, Pixar animator and a fan and friend of Miyazaki, would oft sit with his staff and spotter Miyazaki'south work when encountering story problems. After seeing Spirited Away Lasseter was ecstatic.[36] Upon hearing his reaction to the film, Disney CEO Michael Eisner asked Lasseter if he would be interested in introducing Spirited Away to an American audience. Lasseter obliged past like-minded to serve equally the executive producer for the English adaptation. Following this, several others began to join the projection: Beauty and the Animate being co-manager Kirk Wise and Aladdin co-producer Donald W. Ernst joined Lasseter equally manager and producer of Spirited Away, respectively.[36] Screenwriters Cindy Davis Hewitt and Donald H. Hewitt penned the English-linguistic communication dialogue, which they wrote in order to match the characters' original Japanese-language lip movements.[11]

The cast of the film consists of Daveigh Chase, Jason Marsden, Suzanne Pleshette (in her concluding moving picture office before her expiry in January 2008), Michael Chiklis, Lauren Holly, Susan Egan, David Ogden Stiers and John Ratzenberger (a Pixar regular). Advertising was limited, with Spirited Away existence mentioned in a small scrolling section of the film section of Disney.com; Disney had sidelined their official website for Spirited Away [36] and given the picture a comparatively small promotional budget.[24] Marc Hairston argues that this was a justified response to Studio Ghibli'south retentivity of the merchandising rights to the motion-picture show and characters, which limited Disney'due south power to properly marketplace the film.[24]

Themes [edit]

Supernaturalism [edit]

The major themes of Spirited Abroad, heavily influenced by Japanese Shinto-Buddhist folklore, center on the protagonist Chihiro and her liminal journey through the realm of spirits. The central location of the motion-picture show is a Japanese bathhouse where a great multifariousness of Japanese folklore creatures, including kami, come up to bathe. Miyazaki cites the solstice rituals when villagers call along their local kami and invite them into their baths.[8] Chihiro as well encounters kami of animals and plants. Miyazaki says of this:

In my grandparents' fourth dimension, it was believed that kami existed everywhere – in copse, rivers, insects, wells, anything. My generation does not believe this, merely I like the idea that nosotros should all treasure everything because spirits might be there, and we should treasure everything because in that location is a kind of life to everything.[viii]

Chihiro's archetypal entrance into another world demarcates her status as 1 somewhere betwixt child and adult. Chihiro also stands outside societal boundaries in the supernatural setting. The utilise of the discussion kamikakushi (literally 'subconscious by gods') within the Japanese title, and its associated folklore, reinforces this liminal passage: "Kamikakushi is a verdict of 'social death' in this world, and coming back to this world from Kamikakushi meant 'social resurrection.'"[37]

Additional themes are expressed through No-Face, who reflects the characters who surround him, learning by example and taking the traits of whomever he consumes. This nature results in No-Face'south monstrous rampage through the bathhouse. After Chihiro saves No-Face with the emetic dumpling, he becomes timid once more. At the end of the film, Zeniba decides to take intendance of No-Confront and so he tin can develop without the negative influence of the bathhouse.[38]

Fantasy [edit]

The motion-picture show has been compared to Lewis Carroll'southward Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, every bit the stories have some elements in mutual such as beingness ready in a fantasy globe, the plots including a disturbance in logic and stability, and there existence motifs such as food having metamorphic qualities; though developments and themes are non shared.[39] [40] [41] Amidst other stories compared to Spirited Away, The Wonderful Sorcerer of Oz is seen to be more closely linked thematically.[40]

Yubaba has many similarities to the Coachman from the 1940 film Pinocchio, in the sense that she mutates humans into pigs in a similar way that the boys of Pleasure Island were mutated into donkeys. Upon gaining employment at the bathhouse, Yubaba's seizure of Chihiro'southward true name symbolically kills the child,[42] who must then assume adulthood. She then undergoes a rite of passage co-ordinate to the monomyth format; to recover continuity with her past, Chihiro must create a new identity.[42]

Traditional Japanese civilization [edit]

Spirited Abroad contains disquisitional commentary on modern Japanese guild concerning generational conflicts and environmental problems.[43] Chihiro has been seen equally a representation of the shōjo, whose roles and credo had inverse dramatically since post-war Japan.[43] Merely as Chihiro seeks her past identity, Japan, in its anxiety over the economic downturn occurring during the release of the moving picture in 2001, sought to reconnect to past values.[42] In an interview, Miyazaki has commented on this nostalgic chemical element for an quondam Nihon.[44]

Western consumerism [edit]

Accordingly, the film tin can be partly understood as an exploration of the effect of greediness and Western consumerism on traditional Japanese culture.[45] For instance, Yubaba is stylistically unique within the bathhouse, wearing a Western apparel and living amid European décor and furnishings, in contrast with the minimalist Japanese manner of her employees' quarters, representing the Western backer influence over Japan in its Meiji period and beyond. Along with its function within the ostensible coming of historic period theme, Yubaba'southward act of taking Chihiro's name and replacing it with Sen (an alternate reading of chi, the first character in Chihiro's name, lit. 'one m'), can be thought of equally symbolic of capitalism's single-minded concern with value.[43]

The Meiji blueprint of the abandoned theme park is the setting for Chihiro'southward parents' metamorphosis – the family arrives in an imported Audi auto and the father wears a European-styled polo shirt, reassuring Chihiro that he has "credit cards and cash," before their morphing into literal consumerist pigs.[46] [ unreliable source? ] [ failed verification ] Miyazaki has stated:

Chihiro's parents turning into pigs symbolizes how some humans get greedy. At the very moment Chihiro says at that place is something odd about this boondocks, her parents turn into pigs. There were people that "turned into pigs" during Japan'southward bubble economy (consumer order) of the 1980s, and these people still haven't realized they've become pigs. Once someone becomes a hog, they don't return to being human but instead gradually showtime to have the "body and soul of a hog". These people are the ones saying, "We are in a recession and don't have enough to consume." This doesn't just apply to the fantasy world. Mayhap this isn't a coincidence and the food is actually (an illustration for) "a trap to catch lost humans."[45]

Still, the bathhouse of the spirits cannot be seen equally a identify free of ambivalence and darkness.[47] Many of the employees are rude to Chihiro because she is man, and abuse is ever-nowadays;[43] it is a identify of backlog and greed, every bit depicted in the initial appearance of No-Face.[48] In stark contrast to the simplicity of Chihiro's journeying and transformation is the constantly chaotic carnival in the background.[43]

Environmentalism [edit]

In that location are two major instances of allusions to environmental issues within the movie. The offset is seen when Chihiro is dealing with the "stink spirit". The stink spirit was really a river spirit, but it was and so corrupted with filth that one couldn't tell what it was at starting time glance. It merely became make clean again when Chihiro pulled out a huge amount of trash, including car tires, garbage, and a wheel. This alludes to man pollution of the environment, and how people tin can carelessly toss away things without thinking of the consequences and of where the trash volition go.

The second innuendo is seen in Haku himself. Haku does not remember his proper noun and lost his past, which is why he is stuck at the bathhouse. Eventually, Chihiro remembers that he used to be the spirit of the Kohaku River, which was destroyed and replaced with apartments. Because of humans' need for development, they destroyed a role of nature, causing Haku to lose his home and identity. This can be compared to deforestation and desertification; humans tear down nature, cause imbalance in the ecosystem, and demolish animals' homes to satisfy their desire for more space (housing, malls, stores, etc.) but do not think about how information technology tin affect other living things.[49]

Release [edit]

Box office and theatrical release [edit]

Spirited Away was released theatrically in Japan on 20 July 2001 by distributor Toho. Information technology grossed a record ¥1.6 billion ($xiii.1 one thousand thousand) in its outset three days, beating the previous record set by Princess Mononoke.[50] It was number one at the Japanese box office for its offset 11 weeks and spent 16 weeks there in total.[51] After 22 weeks of release and after grossing $224 one thousand thousand in Japan, it started its international release, opening in Hong Kong on 13 December 2001.[52] Information technology was the get-go film that had grossed more than $200 million at the worldwide box function excluding the United States.[53] [54] Information technology went on to gross ¥30.four billion to get the highest-grossing moving-picture show in Japanese history, according to the Motility Film Producers Association of Japan.[55] Information technology also set the all-time attendance record in Nippon, surpassing the sixteen.8 million tickets sold past Titanic.[56] Its gross at the Japanese box office has since increased to ¥31.68 billion, as of 2020[update].[57] [58]

In February 2002, Wild Agglomeration, an international sales company that had recently span-off from its former parent StudioCanal, picked upwards the international sale rights for the motion picture outside of Asia and France.[59] The company would then on-sell it to independent distributors across the earth. On April 13, 2002, The Walt Disney Company acquired the Taiwanese, Singapore, Hong Kong, French and North American sale rights to the film, alongside Japanese Home Media rights.[60]

Disney's English dub of the film supervised by Lasseter, premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival on seven September 2002[61] and was later released in the United States on 20 September 2002. The motion picture grossed $450,000 in its opening weekend from 26 theatres. Spirited Away had very little marketing, less than Disney'south other B-films, with a maximum of 151 theatres showing the film in 2002.[24] Afterwards the 2003 Oscars, it expanded to 714 theatres. It ultimately grossed around $10 million past September 2003.[62] Outside of Japan and the United States, the movie was moderately successful in both South Korea and French republic where it grossed $xi 1000000 and $six million, respectively.[63] In Argentina, information technology is in the top x anime films with the most tickets sold.[64]

In the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, then-independent based film distributor Optimum Releasing acquired the rights to the movie from Wild Bunch in January 2003.[65] The company then released it theatrically on 12 September 2003.[66] [67] The flick grossed $244,437 on its opening weekend from 51 theatres, and by the end of its theatrical run in October, the film has grossed $one,383,023 in the land.[68]

Nearly 18 years after its original release in Japan, Spirited Away had a theatrical release in China on 21 June 2019. It follows the theatrical Red china release of My Neighbour Totoro in December 2018.[69] The delayed theatrical release in China was due to long-standing political tensions between China and Nihon, but many Chinese became familiar with Miyazaki's films due to rampant video piracy.[70] It topped the Chinese box function with a $28.eight-million opening weekend, beating Toy Story four in China.[71] In its 2d weekend, Spirited Away grossed a cumulative $54.8 one thousand thousand in China, and was second merely behind Spider-Man: Far From Home that weekend.[72] As of 16 July 2019[update], the motion-picture show has grossed $seventy million in China,[73] bringing its worldwide total box office to over $346 meg as of 8 July 2019[update].[74]

Spirited Abroad 'southward worldwide box office total stands at US$395,802,070[a]

Habitation media [edit]

Spirited Away was first released on VHS and DVD formats in Nihon by Buena Vista Home Entertainment on xix July 2002.[75] The Japanese DVD releases include storyboards for the moving-picture show and the special edition includes a Ghibli DVD player.[76] Spirited Abroad sold v.5one thousand thousand domicile video units in Nihon by 2007,[77] and currently[ when? ] holds the tape for most home video copies sold of all-time in the state.[78] The movie was released on Blu-ray by Walt Disney Studios Japan on 14 July 2014, and DVD was as well reissued on the same day with a new HD primary, alongside several other Studio Ghibli movies.[79] [80]

In North America, the film was released on DVD and VHS formats past Walt Disney Dwelling Entertainment on 15 April 2003.[81] The attention brought by the Oscar win resulted in the film becoming a strong seller.[82] The bonus features include Japanese trailers, a making-of documentary which originally aired on Japan Television, interviews with the North American vocalism actors, a select storyboard-to-scene comparison and The Art of Spirited Away, a documentary narrated by histrion Jason Marsden.[83] The movie was released on Blu-ray by and North America by Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment on sixteen June 2015.[84] GKIDS and Shout! Factory re-issued the movie on Blu-ray and DVD on 17 October 2017 post-obit the expiration of Disney's previous deal with Studio Ghibli in the land.[85] On 12 November 2019, GKIDS and Shout! Mill issued a Due north-America-exclusive Spirited Away collector'south edition, which includes the motion picture on Blu-ray, and the film'southward soundtrack on CD, also as a twoscore-page book with statements past Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki, and essays by film critic Kenneth Turan and film historian Leonard Maltin.[86] [87]

In the United Kingdom, the film was released on DVD and VHS as a rental release through independent distributor High Fliers Films PLC following the film'due south limited theatrical release. Information technology was later on officially released on DVD in the UK on 29 March 2004, with the distribution being done by Optimum Releasing themselves.[88] In 2006, the DVD was reissued every bit a single-disc release (without the second one) with packaging matching other releases in Optimum's "The Studio Ghibli Collection" range.[89] The and then-renamed StudioCanal UK released the movie on Blu-ray on 24 November 2014, A British 20th Anniversary Collector's Edition, like to other Studio Ghibli anniversary editions released in the Britain, was released on 25 Oct 2021.[90]

Along with the rest of the Studio Ghibli films, Spirited Away was released on digital markets in the United States for the get-go time, on 17 December 2019.

Reception [edit]

Critical response [edit]

Spirited Away has received significant critical success on a broad scale. On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a 97% blessing rating based on 190 reviews, with an average rating of 8.60/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "Spirited Away is a dazzling, enchanting, and gorgeously fatigued fairy tale that will leave viewers a little more than curious and fascinated by the world around them."[91] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 96 out of 100 based on 41 critics, indicating "universal acclamation."[12]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Lord's day-Times gave the film a full four stars, praising the piece of work and Miyazaki'south direction. Ebert also said that Spirited Away was one of "the year's all-time films", as well as adding information technology to his "Great Movies" list.[92] Elvis Mitchell of The New York Times positively reviewed the flick and praised the animation sequences. Mitchell drew a favorable comparison to Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass, and wrote that Miyazaki's "movies are equally much near moodiness as mood" and that "the prospect of animated figures' non being what they seem -- either spiritually or physically -- heightens the tension."[41] Derek Elley of Variety said that Spirited Abroad "can be enjoyed by sprigs and adults alike" and praised the animation and music.[93] Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times praised Miyazaki's direction and the vocalisation acting, besides as saying that the film is the "product of a tearing and fearless imagination whose creations are unlike annihilation a person has seen before."[94] Orlando Sentinel 'south critic Jay Boyar as well praised Miyazaki's direction and said the movie is "the perfect pick for a child who has moved into a new home."[95]

In 2004, Cinefantastique listed the movie as one of the "10 Essential Animations".[96] In 2005, Spirited Away was ranked by IGN equally the 12th-best animated film of all time.[97] The film is also ranked number 9 of the highest-rated movies of all time on Metacritic, being the highest rated traditionally animated moving-picture show on the site. The film ranked number ten in Empire magazine's "The 100 All-time Films of World Movie house" in 2010.[98] In 2010, Rotten Tomatoes ranked it as the 13th-all-time animated pic on the site,[99] and in 2012 as the 17th.[100] In 2019, the site considered the film to be #1 amid 140 essential animated movies to watch.[101] In 2021 the moving picture was ranked at number 46 on Time Out magazine's list of "The 100 All-time Movies of All Time".[102]

In his book Otaku, Hiroki Azuma observed: "Between 2001 and 2007, the otaku forms and markets quite rapidly won social recognition in Japan," and cites Miyazaki's win at the University Awards for Spirited Away among his examples.[103] [ failed verification ]

Accolades [edit]

| Yr | Laurels | Category | Recipient | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Animation Kobe | Theatrical Film Honour | Spirited Away | Won |

| Blue Ribbon Awards | All-time Film | Spirited Away | Won | |

| Mainichi Film Awards | Best Film | Spirited Away | Won | |

| All-time Animated Picture show | Spirited Away | Won | ||

| Best Director | Hayao Miyazaki | Won | ||

| 2002 | 25th Japan University Honor | Best Film | Spirited Abroad | Won[104] |

| Best Song | Youmi Kimura | Won[104] | ||

| 52nd Berlin International Picture show Festival | Golden Bear | Spirited Away | Won (together with Bloody Sunday) [105] | |

| Cinekid Festival | Cinekid Film Honour | Spirited Away | Won (together with The Little Bird Boy) [106] | |

| 21st Hong Kong Film Awards | Best Asian Picture | Spirited Away | Won[107] | |

| Tokyo Anime Award | Animation of the Year | Spirited Abroad | Won | |

| Best Art Direction | Yôji Takeshige | Won | ||

| Best Character Design | Hayao Miyazaki | Won | ||

| Best Director | Hayao Miyazaki | Won | ||

| Best Music | Joe Hisaishi | Won | ||

| All-time Screenplay | Hayao Miyazaki | Won | ||

| All-time Voice Histrion | Rumi Hiiragi as Chihiro | Won | ||

| Notable Entry | Hayao Miyazaki | Won | ||

| Utah Pic Critics Association Awards | All-time Picture | Spirited Abroad | Won | |

| Best Director | Hayao Miyazaki Kirk Wise (English version) | Won | ||

| All-time Screenplay | Hayao Miyazaki Cindy Davis Hewitt (English accommodation) Donald H. Hewitt (English adaptation) | Won | ||

| Best Non-English Linguistic communication Film | Japan | Won | ||

| National Board of Review | National Board of Review Accolade for Best Animated Picture | Spirited Abroad | Won | |

| New York Film Critics Online | Best Animated Feature | Spirited Away | Won | |

| 2003 | 75th Academy Awards | Best Animated Feature | Spirited Abroad | Won[108] |

| 30th Annie Awards | Annie Award for Best Animated Feature | Spirited Away | Won | |

| Directing in an Animated Characteristic Production | Hayao Miyazaki | Won | ||

| Annie Award for Writing in a Feature Production | Hayao Miyazaki | Won | ||

| Annie Award for Music in a Feature Production | Joe Hisaishi | Won | ||

| 8th Critics' Option Awards | All-time Blithe Feature | Spirited Away | Won | |

| 29th Saturn Awards | Best Animated Film | Spirited Away | Won | |

| Saturn Award for Best Writing | Hayao Miyazaki Cindy Davis Hewitt (English adaptation) Donald H. Hewitt (English language accommodation) | Nominated | ||

| Saturn Honor for Best Music | Joe Hisaishi | Nominated | ||

| 7th Golden Satellite Awards | Best Animated or Mixed Media Feature | Spirited Away | Won | |

| Amsterdam Fantastic Film Festival | Silver Scream Honor | Spirited Away | Won | |

| Christopher Awards | Characteristic Film | Spirited Away | Won | |

| 2004 | 57th British University Motion picture Awards | All-time Film Not in the English Language | Spirited Away | Nominated |

Stage product [edit]

A stage production of Spirited Abroad was announced in February 2021 with a world premiere planned in Tokyo on Feb 28, 2022. The adaption volition be written and directed past John Caird, with Toho as the product company, with Studio Ghibli's blessing. The role of Chihiro volition be played past both Kanna Hashimoto and Mone Kamishiraishi.[109] [110]

| Main Bandage | ||

|---|---|---|

| Character name | Actor (Double Bandage) | |

| Chihiro (千尋) | Kanna Hashimoto | Mone Kamishiraishi |

| Haku (ハク) | Kotarou Daigo | Hiroki Miura |

| Kaonashi (顔無し) | Koharu Sugawara | Tomohiko Tsujimoto |

| Rin (リン) | Miyu Sakihi | Fuu Hinami |

| Kamajī (釜爺) | Tomorowo Taguchi | Satoshi Hashimoto |

| Yubāba (湯婆婆) / Zenība (銭婆) | Mari Natsuki | Romi Park |

Run across also [edit]

- 2000s in film

- Isekai

- Listing of highest-grossing anime films

- List of highest-grossing films in Japan

- Noppera-bō: Japanese "no-confront" spirit

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c Spirited Away 's Worldwide Box Office:

- Original Run including re-release until Studio Ghibil Fest 2020 – U.s.a.$395,580,000 (¥47,030,975,000)[4]

- 2021 re-release in Spain – €186,772[5] (United states$222,070)[6]

- ^ Lit. "ane one thousand".

- ^ Lit. "flourishing swift-flowing amber [river] god".

- ^ Lit. "bathhouse granny".

- ^ Lit. "money granny".

- ^ Lit. "boiler grandad".

- ^ a b Lit. "faceless".

- ^ Lit. "bluish frog".

- ^ Lit. "reception desk frog".

- ^ Lit. "Bully White Lord".

References [edit]

- ^ "Spirited Away (PG)". British Board of Film Nomenclature. 14 August 2003. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ^ a b c The Making of Hayao Miyazaki'south "Spirited Away" – Part one Archived 12 March 2009 at the Wayback Car. Jimhillmedia.com.

- ^ Herskovitz, Jon (15 Dec 1999). "'Mononoke' creator Miyazaki toons up pic". Variety. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Harding, Daryl. "Demon Slayer: Mugen Train Overtakes Your Name to Become second Highest-Grossing Anime Film of All Fourth dimension Worldwide". Crunchyroll. Archived from the original on xv February 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ España, Taquilla (24 May 2021). "El viaje de Chihiro". TAQUILLA ESPAÑA (in European Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Spirited Away 2021 Re-release (Espana)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved xxx June 2021.

- ^ "Sen To Chihiro No Kamikakushi Archived eleven April 2013 at WebCite". http://www.bcdb.com, xiii May 2012

- ^ a b c d Boyd, James W. and Tetsuya Nishimura. [2004] 2016. "Shinto Perspectives in Miyazaki's Anime Motion-picture show 'Spirited Away' (PDF) Archived 20 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine." Periodical of Religion & Film 8 (3):Commodity 4.

- ^ Sunada, Mami (Director) (16 November 2013). 夢と狂気の王国 [The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness] (Documentary) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Studio Ghibli. Archived from the original on seven July 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014. Interview with Toshio Suzuki

- ^ "xv Fascinating Facts About Spirited Away". mentalfloss.com. 30 March 2016. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ a b Turan, Kenneth (twenty September 2002). "Under the Spell of 'Spirited Away'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 19 June 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Spirited Away (2002)". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 14 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ Pineda, Rafael Antonio (13 December 2020). "Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba Motion-picture show Is 1st Since Spirited Away to Earn 30 Billion Yen". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on xv December 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "The 50 Best Movies of the Decade (2000–2009)". Paste. iii November 2009. Archived from the original on 12 Dec 2011. Retrieved 14 Dec 2011.

- ^ "Flick Critics Choice the Best Movies of the Decade". Metacritic. iii January 2010. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ^ "Top 100 Blitheness Movies". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on ix May 2013. Retrieved six May 2013.

- ^ Harding, Daryl. "Toho Updates Spirited Abroad Lifetime Japanese Box Role Gross equally Demon Slayer: Mugen Train Inches Closer to #ane". Crunchyroll. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "The 75th Academy Awards (2003)". University of Picture show Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 28 Nov 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ "Watch This: Top l films for children up to the historic period of 14". Archived 25 May 2012.

- ^ "The 21st Century's 100 greatest films". BBC. 23 August 2016. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017.

- ^ "The 25 Best Films of the 21st Century Then Far". The New York Times. 9 June 2017. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d east Miyazaki on Spirited Away // Interviews // Archived 25 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Nausicaa.net (xi July 2001).

- ^ Hill, Jim (14 April 2020). "The Making of Hayao Miyazaki's "Spirited Away" – Role 1". jimhillmedia.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Spirited Away past Miyazaki". FPS Magazine. Archived from the original on 19 May 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- ^ "Notoya in Ginzan Onsen stop business for renovation. | Tenkai-nihon:Cool Japan Guide-Travel, Shopping, Style, J-popular". Tenkai-nihon. 1 July 2010. Archived from the original on 28 October 2012. Retrieved half-dozen May 2013.

- ^ "Focus Newspaper: Hayao Miyazaki, 72-year-old Mischievous Youngster (from 3:00 marking)". TVBS Telly. Archived from the original on x July 2015. Retrieved v July 2015.

- ^ Dogo Onsen Archived 13 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine japan-guide.com

- ^ Miyazaki's Spirited Abroad (CD). Milan Records. ten September 2002. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015.

- ^ "第56回 日本映画大賞 (56th Japan Movie Awards)". Mainichi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ "Results From Tokyo Anime Fair Awards". Anime Nation. 19 February 2002. Archived from the original on vi October 2014. Retrieved ane September 2013.

- ^ "The 17th Japan Gilded Disc Award 2002". Recording Manufacture Clan of Japan. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ "晩夏(ひとりの季節)/いのちの名前 (The name of life/tardily summer)". Ayaka Hirahara. Archived from the original on fifteen Dec 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ a b c "Yumi Kimura". Nausicaa.internet. Archived from the original on xx April 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ "第43回日本レコード大賞 (43rd Nihon Record Honor)". Japan Composer'due south Association. Archived from the original on 9 October 2003. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ "久石譲 千と千尋の神隠し イメージアルバム (Joe Hisaishi Spirited Away Image Anthology)". Tokuma Japan Communications. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ a b c The Making of Hayao Miyazaki's "Spirited Away" – Part 3 Archived 17 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Jimhillmedia.com.

- ^ Reider, Noriko T. 11 Feb 2009. "Spirited Away: Film of the Fantastic and Evolving Japanese Folk Symbols." Film Criticism 29(3):iv–27.

- ^ Gomes, Paul. "Lesson Plan – Spirited Away" (PDF). UHM. Archived from the original (PDF) on v November 2013. Retrieved 12 Baronial 2013.

- ^ Sunny Bay (22 June 2016). "Across Wonderland: 'Spirited Abroad' Explores The Significance of Dreams in the Real World". moviepilot.com. Archived from the original on xiv Baronial 2016.

- ^ a b "Influences on the Moving picture | Spirited Away". SparkNotes. 2004. Archived from the original on 14 August 2016.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Elvis (twenty September 2002). "Motion picture Review – Spirited Abroad". The New York Times. Archived from the original on xi May 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2011.

- ^ a b c Satoshi, Ando. 11 February 2009. "Regaining Continuity with the Past: Spirited Away and Alice's Adventures in Wonderland." Bookbird 46(i):23–29. doi:10.1353/bkb.0.0016.

- ^ a b c d e Napier, Susan J. eleven February 2009. "Matter Out of Place: Funfair, Containment and Cultural Recovery in Miyazaki's Spirited Abroad." Journal of Japanese Studies 32(two):287–310. doi:10.1353/jjs.2006.0057.

- ^ Mes, Tom (7 January 2002). "Hayao Miyazaki Interview". Midnight Heart. Archived from the original on 2 August 2009. Retrieved one August 2009.

- ^ a b Gilt, Corey (14 July 2016). "Studio Ghibli letter of the alphabet sheds new lite on Spirited Away mysteries". SoraNews24. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ "HSC Extension form" (PDF). New South Wales Section of Instruction and Grooming. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ^ Thrupkaew, Noy. "Animation Awareness: Why Japan's Magical Spirited Away Plays Well Anywhere." American Prospect thirteen.19: 32–33. Academic OneFile. Gale. 11 February 2009.

- ^ Harris, Timothy. "Seized by the Gods". Quadrant 47.9: 64–67. Academic OneFile. Gale. 11 February 2009.

- ^ Saporito, Jeff. "What does "Spirited Away" say about Environmentalism?". ScreenPrism. Archived from the original on iii March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ Groves, Don (30 July 2001). "Dinos + Ogre = Monster o'seas B.O.". Diversity. p. 12.

- ^ Groves, Don (15 Oct 2001). "'Raider' rules Japan; 'Rouge' rosy in France". Variety. p. fifteen.

- ^ Boland, Michaela (24 December 2001). "'Rings' tolls in vivid B.O. 24-hour interval o'seas". Variety. p. 9.

- ^ Johnson, G. Allen (iii February 2005). "Asian films are grossing millions. Hither, they're either remade, held hostage or released with footling fanfare". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- ^ Groves, Don (22 October 2001). "Romance, laffs boos o'seas B.O.". Variety. p. 12.

- ^ Sudo, Yoko (four June 2014). "'Frozen' Ranks equally Third-Biggest Striking in Japan". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 6 February 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

Walt Disney's Frozen has surpassed ¥21.2 billion (about $212 meg) in box role sales equally of this week and now ranks as the third-highest-grossing pic ever in Japan, according to the company ... Having topped Harry Potter and the Wizard's Stone, Frozen now trails just Titanic, which opened in 1997 and grossed ¥26.2 billion, and Hayao Miyazaki'southward Spirited Away, which opened in 2001 and brought in ¥xxx.4 billion, according to the Movement Picture Producers Association of Japan Inc.

- ^ Groves, Don (1 Oct 2001). "H'wood makes 'Blitz' into Japan". Multifariousness. p. 16.

- ^ Harding, Daryl (fifteen December 2020). "Toho Updates Spirited Away Lifetime Japanese Box Office Gross as Demon Slayer: Mugen Railroad train Inches Closer to #1". Crunchyroll. Archived from the original on iii February 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ 歴代興収ベスト100 [All-time box-part top 100] (in Japanese). Kogyo Tsushinsha. Archived from the original on 8 Baronial 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ "Wild Bunch adds Spirited Away, amongst others". Archived from the original on thirteen September 2021. Retrieved thirteen September 2021.

- ^ "Copyrights to 'Spirited Abroad' sold to Disney". 13 Apr 2002. Archived from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved xviii October 2021.

- ^ Ball, Ryan (nine September 2001). "Spirited Away Premieres at Toronto Int'l Motion-picture show Fest". Blitheness Magazine. Archived from the original on ix Oct 2012. Retrieved two June 2011.

- ^ "Spirited Abroad Box Function and Rental History". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 16 Jan 2006. Retrieved 21 April 2006.

- ^ "Spirited Away – Original Release". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Oliveros, Mariano (23 July 2015). "Los films de anime que lideran la taquilla argentina" (in Spanish). Ultracine. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ "Optimum brings Japanese mega-hit Spirited Away to Britain | News | Screen". Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved xi September 2021.

- ^ Optimum Releasing

- ^ "BBC Collective – Spirited Away". BBC. Archived from the original on thirty November 2005. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ^ "Spirited Away". Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "Hayao Miyazaki'due south 2001 Archetype 'Spirited Away' Finally Gets Release in China". The Hollywood Reporter. 27 May 2019. Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ "These five Studio Ghibli films really should exist released in China". South China Morning Post. 17 Dec 2018. Archived from the original on 25 June 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Coyle, Jake (23 June 2019). "'Toy Story iv' opens big simply below expectations with $118M". AP News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ "Daily Box Office". EntGroup. 30 June 2019. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved i July 2019.

- ^ "Daily Box Office". EntGroup. viii July 2019. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ "Spirited Away – All Releases". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 26 Oct 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ 千と千尋の神隠し (in Japanese). Walt Disney Japan. Archived from the original on xix December 2013. Retrieved 17 Nov 2012.

- ^ "ブエナビスタ、DVD「千と千尋の神隠し」の発売日を7月19日に決定" (in Japanese). AV Watch. 10 May 2002. Archived from the original on xxx July 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ 均, 中村 (23 May 2007). "110万冊無料配布。"ゲドを読む。"の狙いを読む 宮崎吾朗監督作品「ゲド戦記」DVDのユニークなプロモーション". Nikkei Business concern (in Japanese). Nikkei Business concern Publications. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Frozen Dwelling house Video Tops Spirited Away as Fastest to Sell two Million Copies in Nippon". Anime News Network. 14 Baronial 2014. Archived from the original on 14 Baronial 2014. Retrieved 14 Baronial 2014.

- ^ "千と千尋の神隠し|ブルーレイ・DVD・デジタル配信|ディズニー公式". Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "Amazon.co.jp: 千と千尋の神隠し [Blu-ray]: 宮崎駿: DVD". Archived from the original on 3 Feb 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ Conrad, Jeremy (14 March 2003). "Spirited Away". IGN. Archived from the original on 9 Apr 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ Reid, Calvin (28 April 2003). "'Spirited Away' Sells like Magic". Publishers Weekly. Vol. 250, no. 17. Archived from the original on xix December 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ "Studio Ghibli – The Official DVD Website". Disney. Archived from the original on one Baronial 2013. Retrieved one September 2013.

- ^ "Amazon.com: Spirited Away (2-Disc Blu-ray + DVD Combo Pack): Daveigh Chase, Lauren Holly, Michael Chiklis, Suzanne Pleshette, Jason Mardsen, Tara Strong, Susan Egan, John Ratzenberger, David Ogden Stiers, Hayao Miyazaki, Original Story And Screenplay By Hayao Miyazaki: Movies & Television receiver". Amazon. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ Giardina, Carolyn (17 July 2017). "Gkids, Studio Ghibli Ink Home Entertainment Deal". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Bui, Hoai-Tran (13 August 2019). "'Spirited Away' Special Collector'southward Edition Will Be Available For a Limited Time This November". Slashfilm. Archived from the original on 8 Nov 2020.

- ^ "Spirited Away [Collector'due south Edition]". The Studio Ghibli Collection. Los Angeles: GKIDS. ASIN B07W8LJLB3. Archived from the original on xx Baronial 2020. .

- ^ "Spirited Away (2 Discs) (Studio Ghibli Collection)". Play. Archived from the original on nineteen July 2013. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ^ "Optimum Releasing – Spirited Away". Optimum Releasing. Archived from the original on 16 Oct 2013. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ^ Amie, Cranswick (xx July 2021). "StudioCanal announces Spirited Away 20th Anniversary Collector's Edition". Flickering Myth. Archived from the original on 8 Nov 2021. Retrieved 29 Oct 2021.

- ^ "Spirited Away (2002)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on xi October 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (20 September 2002). "Spirited Abroad". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2011.

- ^ Elley, Derek (18 February 2002). "Spirited Away Review". Diversity. Archived from the original on iii February 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2011.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (20 September 2002). "Under the Spell of 'Spirited Abroad'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on nineteen June 2012. Retrieved two September 2011.

- ^ Boyar, Jay (eleven October 2002). "'Spirited Abroad' – A Magic Carpet Ride". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Persons, Dan (February–March 2004). "The Americanization of Anime: x Essential Animations". Cinefantastique. Vol. 36, no. 1. p. 48. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ "The Acme 25 Animated Movies of Best". IGN Entertainment. Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved six May 2010.

- ^ "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema – ten. Spirited Away". Empire. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Best Blithe Films – Spirited Away". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ "All-time Animated Films". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved ii February 2018.

- ^ "140 essential animated movies to watch now Archived 7 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine." Rotten Tomatoes. 2019. Retrieved 28 Baronial 2020.

- ^ "The 100 Best Movies of All Time". 8 April 2021. Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Azuma, Hiroki (10 April 2009). "Preface". Otaku. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Printing. p. xi. ISBN978-0816653515. Archived from the original on nineteen July 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ a b "List of award-winning films at the 25th Japan Academy Awards". Japan Academy Awards Clan (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ "Prizes & Honours 2002". Berlinale. Archived from the original on fifteen Oct 2013. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ^ "'Bird,' 'Spirited' nab child kudos". Variety. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ^ "第21屆香港電影金像獎得獎名單 List of Award Winner of The 21st Hong Kong Film Awards". Hong Kong Moving-picture show Awards. Archived from the original on 5 Baronial 2013. Retrieved 9 Baronial 2013.

- ^ "The 75th Academy Awards (2003) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Movement Motion-picture show Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on thirty November 2011. Retrieved ix Baronial 2013.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (25 February 2021). "'Spirited Away': Hayao Miyazaki's Classic Blithe Oscar Winner To Exist Adapted For The Stage". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ McGee, Oona (10 November 2021). "First look at Studio Ghibli'south new Spirited Away alive-activeness stage play". SoraNews24.com . Retrieved 7 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

Farther reading [edit]

- Boyd, James W., and Tetsuya Nishimura. 2004. "Shinto Perspectives in Miyazaki's Anime Film 'Spirited Abroad'." The Periodical of Religion and Pic eight(2).

- Broderick, Mick (2003). "Intersections Review, Spirited Abroad by Miyazaki'due south Fantasy". Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context (9). Retrieved five June 2016.

- Callis, Cari. 2010. "Zip that Happens is ever Forgotten." In Anime and Philosophy, edited by J. Steiff and T. D. Tamplin. New York: Open up Court. ISBN 9780812697131.

- Cavallaro, Dani (2006). The Animé Fine art of Hayao Miyazaki. Jefferson, North.C.: McFarland & Co. ISBN9780786423699.

- Cooper, Damon (1 November 2010), "Finding the spirit within: a disquisitional analysis of moving-picture show techniques in spirited Away.(Critical essay)", Babel, Australian Federation of Modern Linguistic communication Teachers Associations, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 30(6), ISSN 0005-3503

- Coyle, Rebecca (2010). Fatigued to Sound: Blitheness Film Music and Sonicity. Equinox Publishing. ISBN978-1-84553-352-6.

Drawn to Sound focuses on feature-length, widely distributed films released in the period since Earth War II, from producers in the USA, United kingdom, Japan and French republic-from Animal Farm (1954) to Happy Feet (2006), Yellow Submarine (1968) to Curse of the Were-Rabbit (2005), Spirited Away (2001) and Les Triplettes de Belleville (2003).

- Denison, Rayna (2008). "The global markets for anime: Miyazaki Hayao's Spirited abroad (2001)". In Phillips, Alastair; Stringer, Julian (eds.). Japanese Cinema: Texts and Contexts. Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-32847-0.

- Fielding, Julien R. (2008). Discovering World Religions at 24 Frames Per Second. Scarecrow Press. ISBN978-0-8108-5996-eight.

Several films with a 'cult-like' following are also discussed, such as Fight Club, Princess Mononoke, Spirited Abroad, and Jacob's Ladder.

- Fox, Kit. "Spirited Away". Animerica. Archived from the original on 7 April 2004.

- Galbraith Four, Stuart (2008). The Toho Studios Story: A History and Complete Filmography. Scarecrow Printing. ISBN978-0-8108-6004-ix.

Since its inception in 1933, Toho Co., Ltd., Japan's most famous movie production company and distributor, has produced and/or distributed some of the most notable films ever to come out of Asia, including Seven Samurai, Godzilla, When a Adult female Ascends the Stairs, Kwaidan, Woman in the Dunes, Ran, Shall We Trip the light fantastic toe?, Ringu, and Spirited Away.

- Geortz, Dee (2009). "The hero with the thousand-and-first confront: Miyazaki's girl quester in Spirited away and Campbell's Monomyth". In Perlich, John; Whitt, David (eds.). Millennial Mythmaking: Essays on the Power of Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature, Films and Games. McFarland. ISBN978-0-7864-4562-2.

- Hooks, Ed (2005). "Spirited Abroad". Acting in Blitheness: A Wait at 12 Films. Heinemann Drama. ISBN978-0-325-00705-2.

- Knox, Julian (22 June 2011), "Hoffmann, Goethe, and Miyazaki's Spirited Away.(E.T.A. Hoffmann, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Hayao Miyazaki)(Disquisitional essay)", Wordsworth Circle, Wordsworth Circumvolve, 42 (3): 198(3), doi:x.1086/TWC24043148, ISSN 0043-8006, S2CID 169044013

- Matthews, Kate (2006), "Logic and Narrative in 'Spirited Away'", Screen Education (43): 135–140, ISSN 1449-857X

- Napier, Susan J. (2005). Anime from Akira to Howl's Moving Castle: Experiencing Gimmicky Japanese Animation. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN978-one-4039-7051-0.

- Osmond, Andrew (2008). Spirited away = Sen to Chihiro no kamikakushi. Basingstoke [England]: Palgrave Macmillan on behalf of the British Motion-picture show Institute. ISBN978-1844572304.

- Suzuki, Ayumi. 2009. "A nightmare of capitalist Japan: Spirited Away", Jump Cut 51

- Yang, Andrew. 2010. "The Two Japans of 'Spirited Away'." International Journal of Comic Art 12(i):435–52.

- Yoshioka, Shiro (2008). "Heart of Japaneseness: History and Nostalgia in Hayao Miyazaki's Spirited Abroad". In MacWilliams, Mark Due west (ed.). Japanese Visual Culture: Explorations in the World of Manga and Anime. One thousand.Eastward. Sharpe. ISBN978-0-7656-1601-two.

External links [edit]

- Spirited Away at IMDb

- Spirited Abroad at the TCM Movie Database

- Spirited Away at AllMovie

- Spirited Away at The Big Cartoon DataBase

- Spirited Away (anime) at Anime News Network'due south encyclopedia

- Spirited Away at Box Office Mojo

- Spirited Away at Metacritic

- Spirited Abroad at Rotten Tomatoes

- Spirited Away at the Japanese Movie Database (in Japanese)

- 75th University Awards Winners | Oscar Legacy | Academy of Picture show Arts and Sciences

Princess Monoke and My Neighbor Totoro! Baby Clother

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spirited_Away

0 Response to "Princess Monoke and My Neighbor Totoro! Baby Clother"

Post a Comment